By David Hoffman

“THIS play’s the thing!”

One can easily imagine William Shakespeare declaring, with an Elizabethan Harrumph, this brusque endorsement of the Mosaic Theater’s production of Samuel D. Hunter’s brilliantly

staged play titled “A Case for the Existence of God”– now on stage through early December at the Atlas Performing Arts Center on H Street NE in Washington DC.

But despite the title, one thing is completely clear up front and throughout: this play is distinctly Not a work of theology. It is certainly not a product of the Seminary.

It is is a product of the Soul however. And the Streets. And Stress. And the green-eyed monster, Sex — and jealousy, and dread, and delight, and fear and loathing. All of that About Sex — straight, and otherwise.

And parentage, straight and crooked, and otherwise. And race. And class. And the ever gnawing fear of falling out of an increasingly unsteady and truly precarious perch on the

shakiest lower rungs of the barely middle class. And then sliding slowly — or suddenly, and all at once — into the lower depths of what Karl Marx once labeled with a barely concealed smirk and

shudder as the barely recognizably as human “lumpen-proletariat.”

And also, it’s about Suspicion. And Secrecy. It’s about Suspension — of belief, and of disbelief. Of Sex, Safe, or otherwise. Of Searching. For Something. Of Seeking. But for what? Sin?

Salvation? Yet only Sometimes ever finding it. And the Stamina to keep on looking. At our most hopeful, looking for ways to connect. (As the great English novelist E.M. Forster enjoined us: “Only connect.”)

But unlike “Hamlet,” the Hunter play is not to catch the conscience of anyone, not any King, or any would-be King. (I’m looking at YOU, Donald Trump!)

No, Dear Reader, in this Hunter play, the theatrical thrust of this 5-star, laugh-out-loud, completely hilarious dramedy — aflame with verbal fireworks and jaw-dropping jokes, fired a mile

a minute — is designed to catch the conscience, and the often guilty conscience indeed, of the

audience.

That’s the case, at least, for this reviewer, who was simply way too often squirming and twisting in his seat. And my best guess is clear: So were many others that evening in the Atlas audience

during that standing-ovation-ending performance.

To admit it bluntly, I was simultaneously laughing on the outside — but also wincing painfully on the too tender inside, stung by the deadly terrible accuracy of the play’s two characters —

themselves divided by race and class and sexual orientation — yet nevertheless bound inexorably together. Just exactly like two men drowning and each trying to save the Other, as

well as himself, as they grapple together with challenges like children and home ownership. And fear and hope. And alienation and empathy. Of erotic attraction and anxious arousal. And the

shock and shudder of fear of the vulnerability of any possible sexual encounter. (Spoiler alert: Rightly or wrongly, it never happens.)

In other words, See This Play if you still have the moxie and the mojo to still care about the future of our democracy — and even what’s left of our now threadbare, but still standing though

teetering, Republic. (Yes, I’m looking at YOU, Ben Franklin.)

The premise of the play is simple enough, at least on the surface. But this superficial simplicity is duplicitous. Because beneath this deceitful surface lurks the downward suction of a mighty

psycho-sexual Maelström, the concealed undertow of today’s powerful contending cultural and social and economic — and sexual — forces ensnaring us in everyday life. In psychodynamic

terms it’s the Freudian and Jungian Unconscious, the infamous “Id” itself, in open and ongoing conflict with a precarious anxiety-ridden Superego, and the resulting ferocious struggle to gain

mastery over an unsteady Ego, itself caught in the middle, in utter confusion, between those two contending and contradictory rival forces.

So what’s Hunter’s astonishingly superb play — staged with extraordinary skill under the deft direction of Brazilian emigre Danilo Gambrini — about anyway?

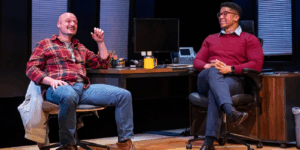

Once again, it’s deceptively simple. Yet it’s also enormously complex. Two struggling fathers — one who’s White, and blue-collar, and the product of an unstable childhood, who’s suddenly

jobless, and he’s divorced, and straight. And the other who’s Black, and college-educated, and middle-class, in a stable white-collar job, and he’s gay! Standing starkly between them is a

socio-economic chasm: as wide as the Grand Canyon, a diploma divide, a class divide, and a sexual divide.

But they share one thing in common: fatherhood. And another thing, where they live, in Twin Falls, Idaho. Hunter himself is Black and gay. He grew up in Moscow, a classic almost textbook case of an arche-typical college town, home of the University of Idaho. He lives now in New York City with his husband and their young adopted daughter. Recipient of a 2014 MacArthur “Genius Grant”

Fellowship, his full-length plays include “The Whale,” for which he also adapted the screenplay for the 2023 film of the same name, directed by Hollywood A-lister Darren Aronofsky, and

starring Brendan Fraser, who won the Best Actor Oscar award for his role as a man self-loathing for being morbidly obese. He is currently Resident Playwright at the Signature Theatre in New

York City. He holds degrees in playwriting from NYU, the Iowa Playwrights Workshop and Juilliard.

The play is rooted in hope but stumbling in anger. Because the men, so apparently unlike each other (at first) on the surface, are nevertheless so like one another beneath the skin. They meet,

at first on highly uneven, contested terrain, connecting through the twin challenges of navigating difficulties posed by home ownership and fatherhood.

Ryan, played with devastating credibility by Lee Osorio, is a man born on the wrong side of the tracks, who grew up poor and is also — very much resentfully — on the wrong side of the

diploma divide. He’s trying, and unsure of the outcome during his divorce proceedings, to keep joint custody of his two-year-old daughter. He is also engaged, with a bad credit record very

much in the way, in an uphill effort to get a bank loan, in order to be able to buy a tract of land once owned by his family.

Meanwhile, Keith, played with separate but clearly equal acting chops by Jaysen Wright, is the bank loan officer who Keith must convince to grant the needed land purchase loan. And it all

starts to go off the rails there. Oh, and Keith is also afraid that he will lose custody of his own foster-care daughter, whom he hopes to be able to adopt, but is facing real discrimination

–because he’s single and (oh yes) he’s gay!

Anguish ensues. Homoerotic attraction endues. Blaming endues. Empathy ensues. Sort of. Jean Paul Sartre, the French playwright and notable 20th century existentialist philosopher, in

his play “L’Enfer, C’est Les Autres” ( Hell Is Other People) was clear: we are damned when we are invariably and inevitably existentially stuck with Other People. ANY Other People. But for

Samuel D. Hunter, this would-be triusm just isn’t true. His case for the possible existence of God comes down to this. When our humanness works, in our connections with other people — as

friends, as families, as lovers — it’s actually Because of Others, not despite them, that we Exist, frail but also free. Captive but captivated. Catastrophic but also cathartic.

This play’s the thing to make this case. Finally, it’s funny as Hell!